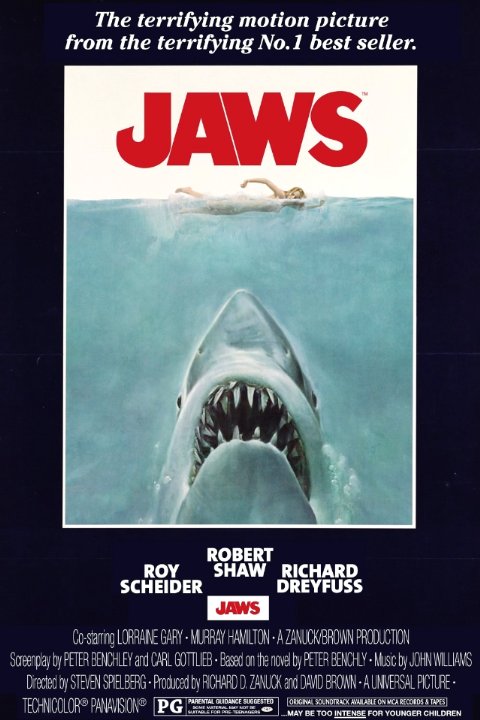

If you are a fan of the movie Jaws then you know that tomorrow is the 40th anniversary of the film’s release (June 20, 1975). Last month I discussed some of the reasons Jaws may have been the greatest horror film ever as part of a follow up to a previous discussion of nature-horror films. What many people don’t know is that quite a bit of “movie magic” went into the making of Jaws.

Let’s take a look at some fun facts about the making of Jaws even hard core fans of the film might not know:

1. Peter Benchley (author of the novel Jaws) spent his summers on Nantucket (where his parents lived). Yet prior to the movie’s filming he had never set foot on Martha’s Vineyard (the location chosen for filming) even though it was literally the island next door.

2. Though Jaws Production Designer Joe Alves immediately fell in love with Martha’s Vineyard it was the island’s underwater charms that sealed the deal. The seabed off Martha’s Vineyard’s eastern shore has a flat sandy bottom crucial for deploying the platform that would move the mechanical shark they had designed.

3. Steven Spielberg was not the first choice to direct Jaws. However when the original director chosen first met with Peter Benchley and the producers he completely alienated Benchley by constantly referring to Jaws as a whale. Producer Richard Zanuck promptly turned to Spielberg, whom he had worked with on the film The Sugarland Express.

4. The mechanical shark was named “Bruce” after Steven Spielberg’s attorney Bruce Ramer.

5. Led by Casting Director Shari Rhodes, the Jaws team ended up using Martha’s Vineyard locals for the overwhelming majority of the roles in the film. In fact, other than Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss, Lorraine Gary, and Murray Hamilton, pretty much everybody else cast in the film was a local – including all of the kids, most of the fishermen, and even Jeffrey Kramer who played Deputy Hendricks.

6. Quint’s boat, the Orca, is actually a 30 foot retired lobster boat named Warlock. The pulpit, mast, and big plate glass windows seen in the movie were all add-ons. This was much to the detriment of the vessel’s seaworthiness. The big plate glass windows were a particular no-no. A wave could easily punch right through the windows and swamp the boat. Surprisingly the Orca actually survived the filming process (a replica was produced for the sinking scenes).

7. Much of the script was reworked during principal filming (which began on May 2, 1974). Carl Gottlieb was the principal writer, but Scheider and Shaw made now legendary contributions to the script. A dozen more had a hand in creating some of the film’s best lines. For instance local resident Henry Carreiro played “Felix” in the film. During the fishing armada scene when Richard Dreyfuss (playing Hooper) asks where he can find a good restaurant Carreiro ad-libbed the line about walking straight ahead (and off the dock). Everyone laughed, and Spielberg decided to go with it. Though Spielberg takes flack for his work on Jaws, he should actually get considerable credit for creating such an open collaborative process and knowing when a good line worked no matter who it came from.

8. Local Vineyard waitress Andrea Muir “played” Chrissie’s hand during the scene when her remains are discovered on the beach. Muir spent hours laying on the beach with her hand made-up to look like it had been floating all night at sea.

9. Robert Shaw modeled Quint’s salty language and personality off two of the most colorful islanders: Craig Kingsbury and Lynn Murphy. Both played key roles in helping with production of the film. Murphy in particular was an expert sailor who time and again bailed out the production team; particularly involving the filming of the movie’s third act.

10. Roy Scheider was slapped in the face seventeen times filming the scene where he is confronted by Alex Kintner’s mother. Luckily he was a former Golden Gloves boxer and could take it.

11. The scene at the dinner table where Roy Scheider and Jay Mello (the six year old local boy playing his son) are copy catting each other initially occurred during a break in filming. Scheider brought it to Spielberg’s attention, and Spielberg liked it so much he put it in the movie.

12. The filming technique “day for night” is used to do most of the night scenes, whereby they actually film during the day but with a special filter on the camera. It was popular in the sixties and seventies, but didn’t work all that well. In Jaws it was more convincing by using techniques such as filming on overcast days and doing additional work in the lab to create the feel of night.

13. Great efforts were put into making the mechanical sharks look realistic. This included spray-painting them with a rubberized paint to make the skin like rough shark skin. The teeth were actually made out of a substance that was similar to rubber. There were two sets, one hard for biting boats and one softer for biting people. The sharks ended up quite impressive looking for the day, but obviously were lacking in many ways. I would love to see what someone could do today instead of relying on all the cartoonish CGI bullshit. Sorry for the editorializing, but sometimes creating real physical special effects works wonders for making a movie an experience. If you don’t believe me then you should go see the new Mad Max (pure movie making with almost no CGI) and then watch the new Jurassic Park (a cartoon fest).

14. Robert Shaw really was hammered off his ass for the Indianapolis scene (all three actors were drinking). And he still rocked it. The man was a genius (plus he could hold his liquor).

15. The dirty ditty sung by Quint about the lady who died at 103 and “for fifteen years she kept her virginity….not a bad record for this vicinity” came from a gravestone Robert Shaw saw in England and added into the script.

16. The guitar player on the beach at the beginning of the film is playing a stylized version of Otis Redding’s “The Dock of the Bay”.

17. The scenes shot on the sinking Orca were mostly done within one hundred yards of the beach.

18. Robert Shaw and his stunt double had to wear a special padded vest to protect themselves from the shark teeth during the filming of Quint’s demise. Though the teeth were rubber they and the jaws snapped hard enough to deliver quite a chomp.

19. Not all water scenes were shot at Martha’s Vineyard. The shark cage sequence was a composite of real sharks shot in Australia and a swimming pool in California. Ben Gardner’s boat discovery scene was also shot in the same pool, as were the scenes of the swimmer’s from below.

20. To get the sea gulls to swarm around after the shark is blown up and Brody and Hooper are kicking to shore potato chips were scattered all over the water (which apparently sea gulls love).

Recent Comments