A few weeks ago I raised the issue of great werewolf transformation scenes. Today we can fondly remember any number of such examples over the past three decades that helped frighten, horrify, and entertain us. But what many people don’t understand today is that in the nearly four decades following the 1941 classic The Wolf Man the werewolf film as a sub-genre of horror had largely floundered. This was for a number of reasons, many of which were caused by the very brilliance of The Wolf Man itself. Directed by George Waggner, featuring the great Lon Chaney Jr. and Claude Raines in starring roles, as well as showcasing Jack Pierce’s pioneering work creating the beast himself; the film on at least an emotional level still stands up today.

Problematically however, The Wolf Man so thoroughly established the Hollywood version of what a werewolf is, how one can defeat such a monster, and what he should look like that the werewolf films that followed ultimately ended up being pale imitations. This was so much so that what many regard as the golden era of B-Movie “creature features” – the 1950’s – almost excluded the werewolf all together (with one notable exception being I Was A Teenage Werewolf starring Michael Landon of Little House on the Prairie fame. It did little to challenge the conventions established by The Wolf Man but ended up being an enjoyable film nevertheless).

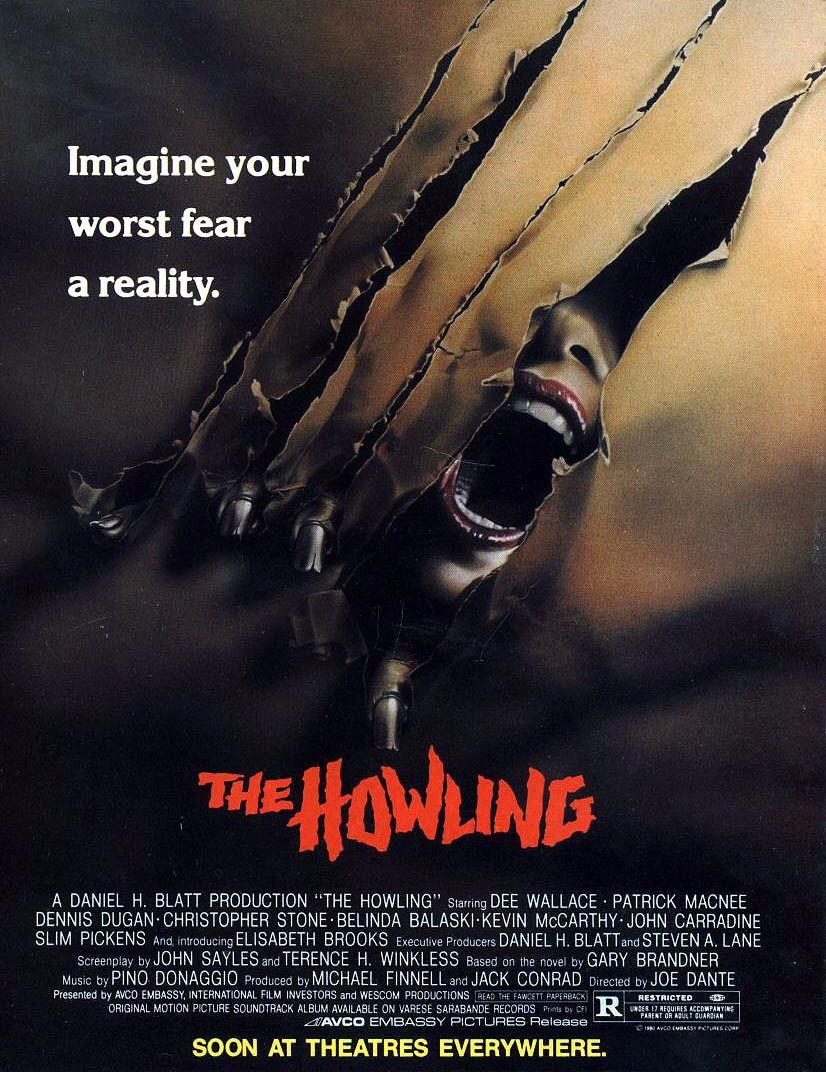

It is thus with that context established that one must regard 1981’s The Howling.

As I mentioned in my last post and though 1981 featured one of the other truly great werewolf films, American Werewolf in London, what many people forget is that The Howling came not only first but lacked the budget of its brethren film. Yet it still ended up producing a near equally satisfying experience for the horror/werewolf aficionado. But the question remains: how?

The answer to that question is of course complex. But at its core it involved a significant reinvention of what the werewolf film should be, and in doing so remains a classic that even younger viewers steeped in CGI effects will find genuinely scary. To that end we must give special credit to Director Joe Dante, his screenwriters John Sayles and Terence Winkless, and a young barely old enough to legally drink special effects wizard named Rob Bottin (himself an understudy to the great Rick Baker).

Dante and Sayles set the tone, crafting a screenplay that featured a humorous semi-comedic and self-deprecating subtext that ended up working brilliantly. John Landis would do the same thing in American Werewolf in London – which truth be told was played much more overtly and to such an extant Landis’ film must be regarded almost as much a comedy as a horror film. What is astonishing about Dante and Sayles’ work however is that they had a successful book (Gary Brandner’s The Howling) from which to craft the story, feel, and theme of the film but instead largely junked it. They started over from scratch (as well as significantly reworked Winkless’ initial drafts of the film version). Consequently, the movie is almost nothing like the book – though both ended up great in their own way (and I recommend that you read the book).

From there Dante filled the cast with a number of superb character actors including Slim Pickens, John Carradine, and Dick Miller among others. In addition he cast the newcomer Elisabeth Brooks; who performed brilliantly as the one character who remained somewhat faithful to the book (the sexy seductress Marsha). Beyond that the film featured additional layers of social commentary poking fun at the media, self-improvement/psychotherapy, and more. Furthermore, Dante, who has a Tarantinoesque reservoir of knowledge regarding 1950’s to 1970’s pulp fiction, paid homage to those who came before him. The film features characters named after great directors and others involved in past werewolf and B-Movie films, plus even includes cameo’s by the great director Roger Corman and Forrest J. Ackerman (he of the well known fanboy magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland).

Moreover, and this is important, Dante and crew did two things that elevated The Howling from merely entertaining to actually reinventing the genre. To that end they made their werewolves not only nearly completely malevolent whether in human or changed form, but also communal. Up until The Howling Waggner’s Wolf Man held an influence so strong that almost nobody had challenged it in any real way. Meaning that Lon Chaney Jr.s anguished portrayal of a guilt ridden Lawrence Talbot had been so brilliant that it had been (as per Hollywood conventions) repeated again and again. Dante cast all of that aside. His werewolves embraced their wolfishness. They reveled in their bestial sexuality and violence, and for the most part accepted themselves for whom they had become. Secondly, the classic werewolf film featured a lone wolf (pun intended), not an entire community of them. This is an aspect of the story that Dante wisely carried over from Brandner’s book. For the audience this was something brand new. And so would be something else….

One of the greatest transformation scenes ever came from The Howling. The scene was so great it served in many ways to overshadow the actual intended climax of the film. Bottin and Baker (who left during filming to work on American Werewolf in London) dramatically raised the stakes in almost a similar way to what the special effects in Star Wars had done for science fiction/space fantasy films.

Though the effects used in The Wolf Man were revolutionary for their day, by the early 1980s they had become decidedly passe. Bottin and Baker rejected the old conventions of applying makeup filmed slowly over time and melded together to produce the effect of shape shifting.

They also rejected the stop-motion animation craze widely present in that era (that had even showed up in The Empire Strikes Back and doesn’t hold up nearly as well as the other special effects techniques of the time). There actually is a stop-motion scene in The Howling and it is not that bad, though it is jarring in comparison to the remainder of the film’s effects. Mercifully that clip is the only one. Other such scenes that were actually filmed but not used were laughably dreadful, and regretfully sucked up enough of the limited budget that the broke production team had to employ actual animation in one scene and to ill effect.

Instead of those techniques Bottin employed the revolutionary use of bladders, mechanical prosthesis, and a whole range of contraptions to create a truly horrifying werewolf:

The Howling is not perfect. The ill advised use of animation to close out a scene of werewolf intercourse/transformation was as mentioned truly lamentable. In addition, and though some viewer’s enjoy the film’s ending, in my opinion the effects actually hindered what could have been an all time classic climax. In this case the film’s final transformation, which began quite horrifying enough and with perhaps Dee Wallace-Stone’s best acting performance of the film (featuring a soul shattering scream of terror followed by genuine sadness and fear) paradoxically was accompanied by a final transformation that left her looking more like a Pomeranian than every other werewolf shown in the film. If Dante and crew could just scrape together a few bucks, re-shoot that final up close shot of her transformed face (substituting in something more like the other werewolves), and put out a new “director’s cut” it would be one instance where I am all for changing part of a classic (ahem Mr. Lucas for the opposite extreme).

Nevertheless, for all of the reasons listed above The Howling is still one of the best werewolf movies ever made. It was groundbreaking for its time, and played an enormous role in ushering in a decade that ended up featuring an inordinate number of the all time best werewolf films. But that is the subject of another post.

Recent Comments